Aikido

Monday |

Tuesday |

Wednesday |

Thursday |

Friday |

Saturday |

| – | 19h15-20h25 | 18h15-19h15 | 19h15-20h25 | – | – |

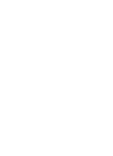

Eric Graf, leader of the Dojo, has already written two books on Aikido:

You can find more writings on Aikido and its related disciplines on our downloads page.

1. The spirit of our school, the spirit of Aikido. The difference between a sport and a martial art

Aikido in one sentence: “Aikido is a martial art of Japanese origin.”

Let us explain this sentence before describing Aikido in more detail, because a thousand interpretations are possible depending on the understanding and vision that everyone has of the terms “Aikido”, “martial art” and “Japanese origin”. Let us agree on how our cultural centers understand these words:

Aikido with a capital ‘A’ and not lowercase. We use this upper case notation to group aikido, hojo, and Japanese yoga Genkikai under one term – Aikido. These three arts are described on this website to allow the novice reader to form an objective image. For those who are already familiar with the word aikido, let’s remember that we group under Aikido more than what is usually understood by the term aikido.

Under “Martial Art” most people imagine a kind of sophisticated combat technique imported from the Orient. We think of Bruce Lee, Chao Lin monks, Ninjas! The French Robert dictionary gives the definition of martial arts: “Traditional combat sports from the Far East.” This is where one starts to get confused! It’s a bad definition. But it dates from a time when the West had to define the term “martial arts” when it had not yet understood its meaning. First, a martial art (we are required to use this term, but forget the dictionary definition) is not a sport! It’s much more than a sport: in a martial art, there is sport but the converse is not true. A martial art contains a philosophy of life, education, rules of ethics and behavior. A martial art shows one of the possible paths for not only physical and spiritual but also social development, for the interior and the exterior.

Practicing a martial art is not only adopting a way of life, it is learning to live better and better on all fronts. And above all: a martial art is without competition! Competition goes against everything a martial art tries to instill, the only real competition that exists in martial art is competition with yourself. Many former martial arts have been simplified in sports precisely in order to introduce competition. With the competition, artificial rules have been introduced to be able to count points and choose a winner. These disciplines have been amputated from any technique or form deemed too violent or too dangerous. Likewise, a large part of the rules of ethics deemed superfluous because of misunderstandings has been eliminated. We started polishing practitioners’ ego, training them to compare themselves. This is completely opposite to the initial martial art of which these disciplines have kept practically only the name. Aikido does not know competition; it is a martial art.

“Of Japanese origin”: indeed the master Morihei Ueshiba gathered under the name of aikido all the facets of the martial art that we practice. In this sense, we can say that Aikido is of Japanese origin. But the origins of Aikido are by far not just Japanese. Morihei Ueshiba was Japanese, just like Leonardo da Vinci Italian, Descartes French or Newton English! However, the influence and knowledge of these people is global. Today, aikido is universal and only keeps its origin in Japan.

If you have to define Aikido in one sentence, this one is clearer:

“Aikido is the study of how to live your life in harmony.”

Let us also give the literal translation of the word Aï-ki-do: Aï, union, harmony, love; ki, the vital energy, the breath of life, the breathing; do, the way. So: the way through the harmonious union of vital energy, hence the above sentence.

2. What is Aikido ?

Learning Aikido only from the perspective of knowing how to fight is like wanting to study a statue while only contemplating the shadow it casts! Thus Aikido is a school of life which is applied at all times and in all situations of life. Its teaching delivers rules essential to social life: we learn indulgence (compassion), the abandonment of arrogance, defusing and avoiding situations of physical, verbal or moral conflict. Thus the knowledge acquired in the Dojo (training room) has as many applications as the practitioner has activities in his life.

Aikido, practiced sincerely, feeds the joy of living, awakens the natural and promotes openness. Aikido is not a religion, even if it includes all religions. It is an art of living, we learn on the one hand to listen to yourself, on the other hand to apply more to understand what constitutes our near and far environment (nature and society).

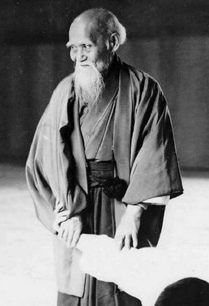

Master Morihei Ueshiba (1893 – 1969) defined in 1929 the principles of Aikido by integrating into techniques of purely physical traditional arts the moral values of the human being.

It was by synthesizing all the techniques of martial arts and philosophical reflections inspired by the principles of non-violence that the Japanese Master Ueshiba created Aikido.

The practice of this non-competitive discipline does not have the final objective of destroying the adversary, nor even deterrence through fear, but on the contrary, an exchange of energy capable of defusing the aggression and evacuating the situation of conflict.

3. What are the benefits of Aikido?

Therefore the regular practice of aikido promotes the circulation of energies as they are understood in shiatsu, Japanese yoga genki kai, seitai, acupuncture or Chinese medicine. We work on the opening of the main energy centers (chakras), as in yoga, in meditation (Aikido is a form of it) or in Hojo (which also develops concentration). It is often said that aikidokas who have been practicing for some time develop excellent skills as masseurs (the sensitivity of the hands increases).

Aikido sharpens the perception of others and events. We can thus learn to feel the moods of other people (anger, sadness, fragility, happiness, …), to feel conflict situations while they are still in the germ state. that is to say before they really come true, and to avoid them, as one avoids a punch.

4. In practice

The principles of Aikido are non-violence and respect for others.

The aikidoka uses dodging as a priority; to avoid any collision, he guides his partner’s attack by controlling him as far as possible to the point of imbalance. At this time, the aikidoka chooses the projection or the immobilization according to the effort that one or the other requires, agreeing at best with the energies deployed and the desired efficiency.

Because it strives for the perfect balance of body and mind, harmony and balance characterize the techniques of Aikido, which, through them, constitutes a method of complete education in accordance with the necessities of our societies.

This “philosophical” martial art contributes to the physical, mental and relational development of the person. Indeed, the practice of this discipline leads to the harmonious development of the body. The execution of the movements requires the acquisition of reflexes, the study of one’s own stability and the search for the attacker’s imbalance as well as the knowledge and use of energy.

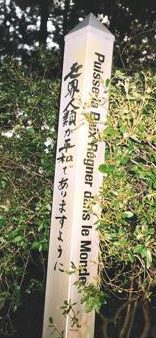

“May there be peace in the World”

Message anchored in the soil of the garden surrounding the aikido founder’s dojo in Iwama near Tokyo in Japan.

(photo: E. Graf)

Aikido does not require a lot of physical force, everyone can practice it, child or adult. His rigorous practice on the tatami constitutes a true school of righteousness and respect. The search for the right attitude at the right time, the purity of the gesture and the thought make this martial art an original discipline where the ideal of perfection combines nature and culture, body and spirit.

Many practitioners come to Aikido for its personal defense aspect, but they quickly realize that it is more than just a set of techniques to subdue a potential opponent. Beyond immediate sporting pleasure, it provides an increased understanding of self and of others as well as an appreciation of human qualities.

5. Progression and levels in Aikido

In aikido, the passage of rank exists but, visually, only the wearing of the hakama (traditional Japanese pants) allows to imagine the progress of a practitioner. The primary purpose of the exams is to give the opportunity to test the knowledge acquired during training. It is good that passing a grade motivates the student to progress. But it must never give rise to a feeling of superiority towards those who have a lower grade or no rank yet (mukyu).

An “extra” belt increases the responsibility of the student. Indeed, it thus becomes responsible for transmitting its knowledge correctly to the least advanced.

There are two types of grades in Aikido:

The KYU (white belts): ten different grades from the 10th Kyu (beginners) to the 1st Kyu (last white belt before the black). The 10th, 9th, 8th and 7th Kyu are held at the dojo and are only awarded to children (adults start at the 6th Kyu), the following grades are held during weekend courses. The technical director of the school is responsible for issuing these grades.

DAN (black belts): the examination is regional, even national, and is recognized by Aikido Switzerland and the Hombu Dojo (world center of aikido in Japan). You must be at least sixteen years of age to sit for the black belt exam.

6. Age to practice

7. Risks

8. How much training per week should you do?

9. Progress of a training

An Aikido training generally includes four stages:

- Short meditation and breathing exercises: their goal being to allow the practitioner to make a break with the daily activities which occupy him, to allow him to refocus, to carry out a return to inner calm, to concentrate on himself .

- The preparation (or warm-up) to warm the body and the joints. It is important to arrive on time for a course in order to participate from the beginning, to avoid accidents.

- The course itself: study of Aikido movements and the martial arts way. The teacher adapts the course to the level of the students and their age.

- The return to calmness: it is a privileged time to rethink the movements learned, it is a short meditation before the final salvation which, often, also symbolizes the return to your (pre-) occupations.

The two salutes before and after each lesson:

The first salute is towards the wall of honor (KAMIZA in Japanese). It is a sign of respect for the place (the dojo), for yourself and for the founder of the discipline.

The second salute is reciprocal between the teacher and the students, as a sign of respect and thanks for what the two parties have learned from each other.

Try our free online introductory course! (in French)